When I was a jock, Billboard was the radio trade publication that everybody read.

Eventually it was supplanted by a much newer publication called Radio and Records.

Why?

- Unlike Billboard, R&R was devoted solely to radio.

- R&R was hipper and move alive than Billboard.

- Billboard looked like (and was) a magazine, while R&R looked like (and pretty much was) a newspaper.

- R&R was exciting to read. When it arrived in Friday’s mail, every radio personality and program director would turn to “Street Talk” (mostly written by some fellow named John Leader) or, depending upon their circumstances, the “Jobs” section.

A few years ago one of my readers told me that at his radio station, management ripped out the “Jobs” section before allowing the programming staff to see the publication.

But Billboard remained popular with radio people for a single reason:

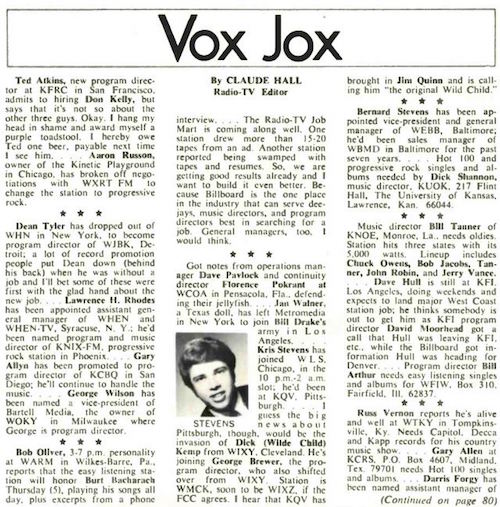

Claude Hall

Claude Hall

Claude was their “radio editor.”

His “Vox Jox” column was every bit as exciting as the newest issue of R&R.

It was obvious that he loved radio and he loved radio people.

Although I’m sure the reason isn’t cloaked in mystery, I never knew precisely why Billboard decided it no longer needed “Vox Jox.”

I could’ve asked Claude, but I never did.

Perhaps long ago he told me what happened, and I’ve managed to file it under “Things I No Longer Remember, Darn It.”

But when Claude left Billboard, the magazine became irrelevant to us radio people.

Claude was Billboard’s radio soul.

When he left, he took the magazine’s soul with it.

R&R had the entire field to itself.

Plucked from Radio Obscurity

I spent my first two years on the air trying to sound like a “good jock.”

Hitting the posts.

Avoiding the dreaded “dead air.”

Trying to make my on-air voice sound deep and ballsy.

As I look back on it now: Trying to add “swagger” to my sound.

Somewhere I still have a tape of terrific contest I created and produced.

The radio contest itself was a big success.

Conceptually and creatively, I’m still proud of it.

But you’ll never hear it, because I so completely failed in my attempt at a deep voiced, Jack McCoy-style VO delivery.

The highly produced promos weren’t narrated by some guy with a deep, dramatic voice that added tension and suspense to the spot.

Anyone — in or out of radio — who hears it instantly realizes it’s some normal-voiced guy trying — unsuccessfully — to sound like one of those dramatic, deep-voiced guys.

As I entered my third year as a radio disc jockey, I decided to stop trying to “sound like everybody else, only better.”

(I wish I’d been aware then of Oscar Wilde’s admonition to “Be yourself. Everyone else is already taken.”)

Rather than showing up for my show and “winging it,” I began to use that program as a opportunity to express myself humorously, comedically and satirically…between the records.

The Radio Personality Competition

Later that year — knowing I didn’t have a chance, but what the heck? — I entered Billboard’s annual awards competition for radio personalities.

But I had a problem.

To enter, I had to submit an aircheck of my show.

The rules specified the aircheck couldn’t run longer than 2 minutes.

Or maybe it was 3 minutes.

I was writing and producing comedy sketches that ran anywhere from 90 seconds to 4 minutes.

==========

Little Known Historical Note

Once upon a time, music radio hosts typically were given a maximum of 7 seconds to squeeze “their own stuff” in between program elements.

==========

There was no way I could demonstrate my mastery of “the basics” (intros, outros, live PSAs, etc.) and include the only thing that made my show special — my produced comedy bits — in a 2-minute recording.

I considered my options.

I could follow the rules, submit a 2-minute aircheck, and have no chance of being anything other than one of hundreds of 2-minute airchecks.

Or I could submit an aircheck that included two original comedy bits while also showing I could do the basics.

In other words, I could submit a 5-minute recording… despite the rules’ clear admonition that it shouldn’t exceed 2 minutes.

I’m guessing mine was the only one among hundreds of entries to run 5 minutes.

I knew that would disqualify me, but it seemed pointless for me to send in a 2-minute entry.

One day the latest Billboard arrived, and it listed the people who’d been selected in each category (market size, format).

Mine was one of the names on that page.

Claude had looked past my lack of respect for rules and, I guess, liked what he heard.

(I think there might’ve been mention of a “judging committee,” but I always had the feeling Claude was the entire committee.)

A year later, I entered the competition again — this time as a major market jock.

Once again, I saw my name among the other jocks from other formats and markets around the country.

Without Claude’s bizarre appreciation for my work, maybe I’d still be a jock in that tiny, unrated market.

The Book About Radio

While he still was writing “Vox Jox,” Claude and his wife, Barbara, shaped a big bunch of his columns into a book:

THIS BUSINESS OF RADIO PROGRAMMING.

Billboard published it via a subsidiary, Watson-Guptill Publications.

It was and remains the best book ever written about radio programming.

I hate to say that.

After all, I’ve written a couple of well-received books about radio myself.

But Claude’s & Barbara’s is the best.

If you have a choice between four years of studying radio in college or reading THIS BUSINESS…, choose the book.

Watson-Guptill allowed the book to go out of print, where it remained for years.

“Let’s Get Your Book Back in Print!”

I believe I spoke in person with Claude only once, when I visited him at his Billboard office in Los Angeles.

But we kept in touch.

Around 1999 I contacted him and said, “Hey, your book is too good not be in print. How about if I publish and market a new edition?”

“I think the publisher still owns the rights to it,” he said.

“Well, they’re not doing anything with it. Since apparently they have no interest in it, why don’t you ask them to reassign the rights to you?”

After months of scratching their heads, trying to think of a reason not to let the rights of a book they’d long ago abandoned revert to the author, the original publisher said yes.

Which I thought was pretty nice of them.

No, We’re Not Going to Use My Copy.

So, Claude had the publishing rights.

But he didn’t have a version in manuscript form, didn’t have the original plates from which it was printed.

I would have to take an existing copy and send it to a specialty publishing house that would break the binding, photograph all the pages, and create a new edition for us.

I sure as heck wasn’t going to give them mine.

So I found a copy of the original on eBay, paid a bunch o’money for it, and had them tear that one apart.

I pay Claude & Barbara a royalty for each copy sold.

After our new version had been on the market for about a year, Claude shocked me by saying, “You’ve already paid us more in royalties than we ever received from Billboard.”

I’m sure Billboard (via Watson-Guptill) had sold a lot more copies than I.

But perhaps they’d been less than generous with their royalty payments.

If you go to Claude’s Facebook Page, you’ll find tributes from some of the many radio people who were inspired, befriended and encouraged by Claude.

Claude Hall passed away barely a week ago — July 7.

Thank you, Claude. For everything.