I don’t know who “invented” song parodies.

I’m sure they were around during Vaudeville, and I’ll wager they existed centuries earlier.

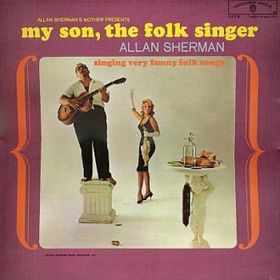

Alan Sherman is recognized by many contemporary song satirists as the father of the current art form.

But it was a song parody that launched the types of nationally produced comedy services that prevail today.

In the early 1980s, Katz Broadcasting put together a team — led by Andy Goodman and The Real Bob James — to create produced comedy features for the five Katz stations across the country.

This small company-within-a-company was dubbed “American Comedy Network,” and they insisted they had no intention of offering the service to non-Katz stations.

From the very beginning, I suspected that’s exactly what they planned to do.

But regardless of their intent, American Comedy Network was changed irrevocably by an integral component of the American communications revolution of the 1980s: the break-up of the telephone company.

In case you’ve already forgotten (or are too young even to remember), the relationship between consumers and “the telephone company” used to be much different than it is today.

For one thing, that’s what it used to be: “The Telephone Company.”

No one had to ask “which one,” because you had no choice.

For most of the country, if you had a telephone in your home or office, you were a customer of Bell Telephone — also known as “Ma Bell” — whether you wanted to deal with Bell or not.

Ma Bell provided your local phone service.

Ma Bell provided your long distance service.

And I’ll bet you almost forgot this part — Ma Bell provided the actual telephones you used.

You didn’t own a telephone; you rented one from Ma Bell… paying for it each and every month, forever.

For the lowest monthly rate, you got an ugly black, rotary telephone.

For a couple of dollars more, you could get a touch tone model.

Or one in a color other than black — but you had to pay extra.

And then the telephone industry was deregulated.

Suddenly, consumers were told they could choose from among a number of long distance carriers.

No longer did they have to rent a telephone from Ma Bell at exorbitant rates; they could go out, buy their own telephone, and plug it into the wall.

Naturally, consumers all over the country responded to the news of their liberation the same way:

They were outraged.

To quote Kris Kristofferson — although as I recall, his song wasn’t really about the phone company — American consumers as a group longed for “the freedom of their chains.”

Sure, as a monopoly Ma Bell made huge profits.

Sure, the company treated its captive customers with disdain.

Sure, their newly emerging competitors — like Sprint and MCI — were offering consumers a chance to save money on long distance calls.

But we felt safe with Ma Bell, benevolent dictator though she was.

People didn’t want to have go out and buy a telephone — especially because Ma Bell’s advertising campaign at the time did its best to scare us into thinking that if we didn’t use one of their telephones, we’d forever find ourselves talking into dead transceivers and, probably, our houses would catch fire, too.

Also, in the mid-1980s, the “alternative” long distance services offered real savings but provided genuinely inferior sound quality.

One of the pervasive problems was “skipping” — that second-and-a- half delay while the signal went from the earthbound transmitter to the satellite and then back earth— which consumers experienced as an annoying “echo” effect, not infrequently hearing their own voices through the receiver as they spoke.

Believe me, people were upset.

And — with perfect timing — ACN recorded a song parody, to the tune of Neil Sedaka’s “Breaking Up Is Hard To Do.”

Now that you know the history of this song (and of the American telephone system), here’s the parody version.

As I recall, the piece was written by The Real Bob James, Andy Goodman, and David Lawrence; the overall music production was done by Bob Rivers.